Claude Code makes several thousand dollars in 30 minutes, with Patrick McKenzie

Today Patrick McKenzie (patio11) walks through a coding session with Claude Code to demonstrate what the fuss is about. The business problem: recovering failed subscription payments that required coordinating APIs across Stripe, Ghost, and email providers, and the surprising experience of watching Claude read documentation, resolve dependency conflicts, and make sensible security choices. The episode offers a pedantic level of detail on why the sharpest technologists use words like “fundamentally transformed” to describe the impact of LLMs on coding.

Thanks to our sponsor: Framer

Building and maintaining marketing websites shouldn’t slow down your engineers. Framer gives design and marketing teams an all-in-one platform to ship landing pages, microsites, or full site redesigns instantly—without engineering bottlenecks. Get 30% off Framer Pro at framer.com/complexsystems.

Timestamps:

(00:00) Intro

(02:21) All engineering work happens in a business context

(03:47) Payment failures briefly taxonomized

(08:25) Now follows a conversation with Claude Code

(20:37) Sponsor: Framer

(21:53) Conversation with Claude Code (continued)

(39:07) My final thoughts on this

(41:15) Wrap

Transcript:

Hideho everyone. This is Patrick McKenzie, better known as patio11 on the Internet.

Today’s a bit of an experimental episode. I have spent quite a bit of time recently doing AI-assisted coding.

[Patrick notes: The bulk of it, as previously discussed on Complex Systems, was in building a game/art project for a conference. You can still play it: IsekaiGame. The experience of spending a month of my year on that project, which was my first de novo development in years and my first experience with modern coding tools, substantially informed my willingness to use them for the subject of today’s episode, which directly touches money in the business I use to pay the mortgage.]

The experience of doing this has, in the view of many technologists I trust, gotten discontinuously better in December, as a result of Claude Code upgrading to Opus 4.5 as the underlying model. [Patrick notes: I’m not a particular partisan for Claude Code over Cursor and OpenAI Codex; it happens to be the tool I reached for this week. I have moderately extensive experience with Cursor and, while I am a frequent user of ChatGPT and OpenAI APIs, have not yet taken Codex for a spin.]

The sharpest technologists I know use words like “fundamentally transformed” to describe the impact of LLMs on coding. Thomas Ptacek, my erstwhile cofounder and an engineer’s engineer, wrote: “All progress on LLMs could halt today, and LLMs would remain the 2nd most important thing to happen over the course of my career.” Andrej Karpathy, one of the founding members of OpenAI, wrote “This is easily the biggest change to my basic coding workflow in ~2 decades of programming and it happened over the course of a few weeks.” (He is referring to the switch from writing code and asking the AI questions to asking the AI to write code and occasionally tweaking it, and not to any particular product.)

If you code every day and have not used modern coding tools like Claude Code, Cursor, or OpenAI’s Codex yet, strongly consider hitting pause now and playing with them for a week or so. It is by far the most important thing you can do for your career and employer this week.

If you don’t code every day and don’t understand what the fuss is about, the rest of this episode is for you. I want to walk through a coding session with Claude Code in a pedantic level of detail. In it, Claude solves a real business problem, involving complex interaction of four computer systems, in a way which multi-billion dollar businesses routinely fail to solve, in 30 minutes.

My contribution to the work was being half-attentive to a chat window after dinner, and while it is definitely engineering work, it exercises relatively few of the muscles that my degree or decades of experience coding developed.

[Patrick notes: We’ve previously had an episode about vibe coding but, to be clear, I consider this simply “the modern practice of software engineering.” As you’ll see in a few minutes, I make many management decisions informed by experience. I just produce very little syntax, terminal commands, and similar relative to the traditional practice of software engineering.]

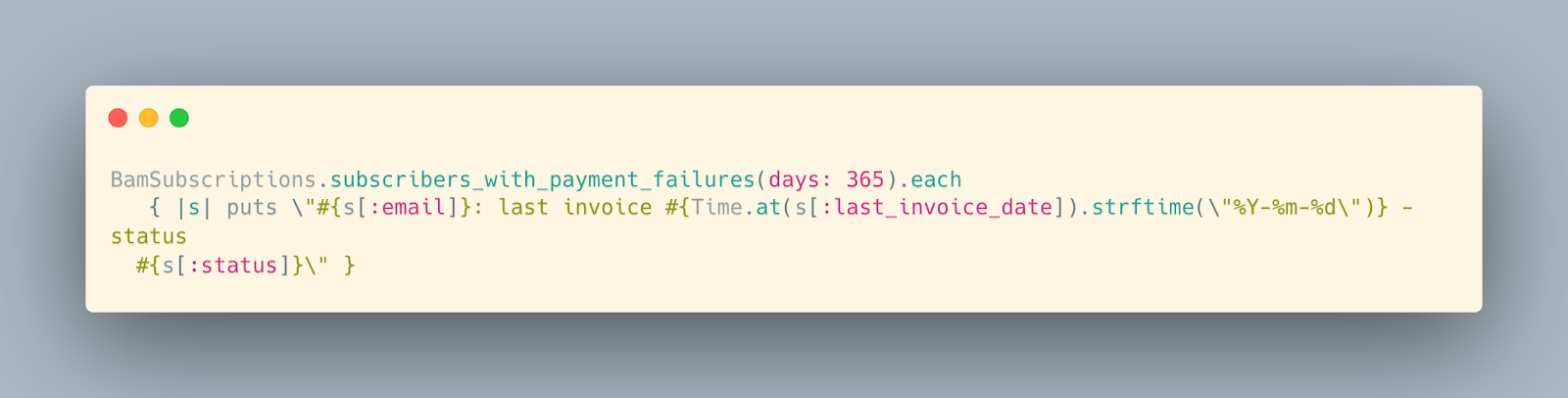

[Patrick notes: If you already basically know the process story I’m going to tell, and just want to read some code for a feel of the coding style and correctness of modern tools circa late January 2026, see this sample, which covers about 60% of the LOC written for this project and is broadly representative of it. If you grok that Ruby code, nothing else the Rails app does will surprise you with regards to these features.]

If you’d prefer not getting deep into a particular example and just want a survey, Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast had an excellent episode with Noah Brier on this topic. It’s the best single artifact for a non-specialist audience about why modern coding tools are a discontinuous advance.

All engineering work happens in a business context

As I often tell people, engineers are not employed to write code. Engineers are employed to increase revenue or reduce costs of businesses. Those are the only two goals.

I run a small business which publishes to the Internet about infrastructure and receives money for doing so. (Definitely not what I think I’ll be doing for the entirety of my remaining career, but it is what pays the bills today.) This podcast is one product of that business. The other main one is Bits about Money, which I describe as a professional journal on the intersection of finance and technology. Other people might describe it as “a paid newsletter.”

BAM memberships are similar in character to supporting one’s local public radio station: there is no paywall, and so the pitch for members is “Pay so this public good continues existing” and not “Pay so you specifically can continue accessing this publication.”

For historical reasons, most BAM members purchase annual memberships, and most of those memberships renew in January. Every year in January, we have a spike of revenue—yay!—and a spike of failed transactions.

I promise we’re returning to AI-assisted coding in a minute, but you have to know a bit about financial infrastructure to understand why the newsletter about financial infrastructure suffers failed transactions.

Briefly, almost all BAM memberships are paid for on personal or company credit cards. Credit cards as an ecosystem tolerate a much higher rate of, industry term of art here, “spurious declines” than you’d expect. We previously had Emily Sands from Stripe on to discuss machine learning approaches to manage this.

Payment failures briefly taxonomized

You can broadly bucket payment failures into three very different scenarios. Scenario 1 is the least common: the customer genuinely does not intend to pay, and has either instructed their bank to block attempts to charge, or is using ghosting you as a way of soft-cancelling their commercial relationship.

Scenario 2, the transient payment failure, is when there is a temporary infrastructure hiccup. A credit card transaction needs to coordinate many more than five computer systems at five firms within a window of a few hundred milliseconds. If any of them blinks during that window, the transaction fails. This happens much more frequently than you would expect for infrastructure that trillions of dollars ride on.

The solution to a transient payment failure, which a business will not generally know is transient, is to simply retry the payment again. I previously worked at Stripe, am presently an advisor there, and they do not necessarily endorse what I say in my own spaces… but I was a user of Stripe long-before and long-after my employment.

And so I know that Stripe will, if you have a setting on your account, transparently try to retry the payment on a configurable schedule. If one of those retries works, then no human has to even know the payment failed temporarily.

Today’s work is about Scenario 3, payment failures which need human interaction to recover from. This could be e.g. a credit card being maxed out, though that is extremely unlikely for my customer base.

[Patrick notes: Bits about Money is read by people from very many walks of life, including a surprising and intimidating-to-me number of policymakers (and their staff). Central banks are not where the money is, though. To the limit of my ability to discern, the typical supporting member is a professional employed in tech or finance, as suggested by either their professional domain name or their emails to me.

Which I say to justify a business calculation: this is not a business which has to care overmuch about debit cards being denied for NSF (insufficient funds). Apologies for explicitly mentioning a material consequence of social class, as I understand that violates a mild taboo among the social class which reads pieces like this, but it is impossible to think rigorously about financial technology while being blind to material consequences of social class.]

They could be a card was reissued after expiry or loss, and the issuer doesn’t participate in automated systems to allow businesses to seamlessly charge the new card. They could be the user switching banks or employers (and thus purchasing card) in the course of the year. Or they could be a bank, for reasons of its own, heuristically detecting this year’s charge as perhaps fraudulent and blocking it, and they’ll continue blocking all attempts until the user tells them to knock it off.

[Patrick notes: I’ve said this a million times but I’ll say it once more. Many people who believe themselves to be well-informed about how credit cards work use canceling a card as a way to cancel e.g. gym memberships. Do not rely on this working for you. While some subscription businesses, including many SaaS companies, are quite lenient with respect to soft cancels, gyms in particular are notorious for enforcing their contractual rights by sending unpaid fees to collection agencies and/or selling that bad debt. And many businesses will happily avail themselves of the technology which lets them charge a card without specifically knowing this number, which the financial industry is very happy to sell them. The pitch is it avoids consequential commercial relationships from getting interrupted due to silly reasons like e.g. a card needing to be reissued. This pitch is a true one, and the bug that people are relying upon to use a card reissue as a way to cancel subscriptions is not a bug the financial industry cares about maintaining backwards compatibility for.]

Scenario 3 interdicts billions of dollars of commerce every year. The typical way businesses deal with it is sending an automated email, telling you a payment failed and asking you to re-enter your payment credentials. In an ideal world, that email lets you one-click no-login to a screen which immediately asks for the new card number and you’re done in 30 seconds. Very, very few businesses, even the largest businesses in the world, successfully execute on this ideal scenario.

This is because their Revenue Operations or Payments teams have ~0 engineering cycles available to them, because this isn’t hugely salient at an executive level. Even if they’re leaving literally tens of millions on the table for want of a few days of engineering work, that fact is not necessarily OBVIOUS to the business.

[Patrick notes: I’ve run my businesses out of Stripe accounts for a decade, used to work at Stripe, and am something of an enthusiast with respect to bookkeeping. I charged off $10,000 of uncollected invoices dating back on average about 2 years this week because no screen in my business specifically showed me an aging graph for small-dollar invoices (subscription revenue) and I hadn’t realized a decade-old legacy setting was causing the final invoice to “leak” into aged-but-presumed-collectible status in my bookkeeping as opposed to deemed-uncollectible. My bookkeeper is going to love me when I say “By the way I need you to papertrail a $10k non-cash one-off loss which arises from revenue that doesn’t actually exist despite me having paid taxes on it last year.”]

If I hadn’t worked in payments, it wouldn’t have been obvious to me, either. The symptom is you expect, for example, 100 users to renew their subscriptions on a particular day. 92 do and the others don’t. If you aren’t intimately familiar with what is going on, you might think “Ahh, those eight people didn’t feel like the last year was valuable for them”, or “they are trying to save money in the coming year”, or whatever folk theory of behavior prevails in your organization.

Now knowing that spurious declines were costing me money every January, did I actually do anything about this? No. Because it required some actual engineering work to deal with. I ballparked it as 1-3 full days for me, and each year in January, I was more concerned with either writing BAM or doing a subscription drive than reversing failed payments. “Maybe next year”, I said, multiple times.

Why is the engineering work here hard? Sending an email about the payment failure is relatively easy. Sending a customized email with a link that gets you directly in to update the payment is more difficult. There are four computer systems in play: my own system, Ghost Pro (the platform BAM is published through), Stripe, which handles all the payment processing and is the system of record for e.g. failed payment attempts, and then Postmark, an email provider.

These each have slightly different views on the elephant. Stripe, for example, knows about payment failures, but not about emails already sent through Postmark. Postmark has no idea who subscribes to BAM; that’s Ghost’s job.

[Patrick notes: The actual published issues of BAM are send by Ghost, not by Postmark. Several different systems are doing functionally equivalent things that physically cannot be consolidated. Ahh, I feel like an enterprise already.]

My system has to reconcile these against each other to determine what to do.

The engineer doing this work needs to use APIs—ways for computer systems to talk to each other programmatically—to coalesce those views into a list of who hasn’t paid successfully, remove users where that is expected (explicitly requested to cancel, etc), construct special URLs to let people in without a login to update information, and then send the emails. And then, money rolls in.

Now follows a conversation with Claude Code

I’m going to try to be clear what I am telling Claude, substantially verbatim, and what Claude is doing or telling me. I will fudge a tiny bit in the interests of comprehensibility or omitting sensitive information.

For example, in the actual development of this and every similar system, an engineer will have to at some point look at so-called production data: real names attached to real email addresses. I will obviously not read those on air. (Thankfully, an engineer does not have to look at real credit card numbers, and indeed cannot in a well-designed system.)

Different scales of enterprises would use different levels of care in having testing environments. This small business does not have a testing environment for BAM: the real users are the only ones we have. And some of the work with Claude in a previous session was being careful because of that lack: we, for example, built a dry-run feature to identify who would get emails before actually sending emails, so that I could eyeball the list for correctness.

Some important context before we get started. Claude can’t “see” a project the same way an engineer sees a project. It relies on an orientation file, Claude.md, that it reads at the start of every session. It can then, in the course of conversation with the user, use what it calls “tools”, like searching for relevant code, reading it, operating the command line (which lets it e.g. restart servers or make test API request or run automated testing tools), and similar. I’ll provide some color commentary about its tool use.

And while Claude does not explicitly remember this fact, because it is a fresh session, it’s important that a few weeks ago I had Claude build a feature for Bits about Money which used the APIs to list upcoming renewals on a dashboard and send emails reminders about upcoming renewals. This is a different business problem than recovering from payment failures, but involves much of the same technical infrastructure, and I explicitly don’t want Claude to reinvent the wheel. So the first thing I do is jog its memory:

Me to Claude:

We're doing the annual Bits about Money subscription renewal month and it seems many subscriptions failed to renew. I think this is likely to be mostly transient payment failures; cards which weren't updated, etc.

I'd like you to enhance the BamSubscriptions class with logic to detect recent (last 30 days, but make it configurable) payment failures which haven't recovered (Stripe might try auto-retry, etc), similar in character to inspecting upcoming BAM renewals. Exclude any where the subscription is in an intentionally canceled state, either originating from the user or from me. After you enhance BamSubscriptions with this, I would appreciate a) a new dashboard page to show these users and b) a rake task to send them an email (similar to the existing subscription reminder email).

You can take a stab at writing the skeleton of that email; I will refine it to be in my voice and make the updates as easy as possible.

Commentary: This “specification” is verbatim, and note how little technical detail it includes. Every bit of software ever written until 12 months ago has to be extremely pedantic about what data sources it is touching, in what bits of code, with what functions, etc. I have given Claude precisely one identifier, the name of a class, BamSubscriptions. I expect Claude to be able, with no other information, to be able to successfully find BamSubscriptions on disk, read it, find the part of it which is about upcoming BAM renewals, and generalize from that previously completed, known-to-work code.

Claude then fires several tool calls. The first one searches on disk for a file named BamSubscriptions. This fails to find the class, which is a CS101 level error. This error is totally inconsequential, because Claude just immediately proceeds to running a wider search, locating bam_subscriptions.rb in the lib subdirectory, right where it put it last time. Claude then reads the file and ponders a bit.

Claude then begins writing new code. It, in a single shot, writes 809 lines of code across seven files. Although I had provided the suggestion that it stagger this development, first doing the bookkeeping work of finding failed payments and then building a dashboard to show those failed payments, a task to send an email to each person, and a skeleton of what that email would say… it just does this all in one go. This is in less than 5 minutes of elapsed wall-clock time.

Claude to me:

I've implemented the payment failure detection and notification system. Here's a summary of the changes:

Changes Made

1. Enhanced lib/bam_subscriptions.rb

Added new methods for payment failure detection:

- subscribers_with_payment_failures(days:) - Finds BAM subscriptions in past_due or unpaid status with failed invoices in the lookback period

- fetch_recent_invoices(subscription_id) - Gets detailed invoice data including failure reasons

- extract_payment_error(invoice) - Translates Stripe error codes into human-readable messages (e.g., "Card

declined: insufficient funds")

- payment_failures_with_details(days:) - Enriched data for dashboard display including invoice URLs and next retry times

- Duplicate prevention via local file tracking and Postmark API checks (similar pattern to renewal reminders)

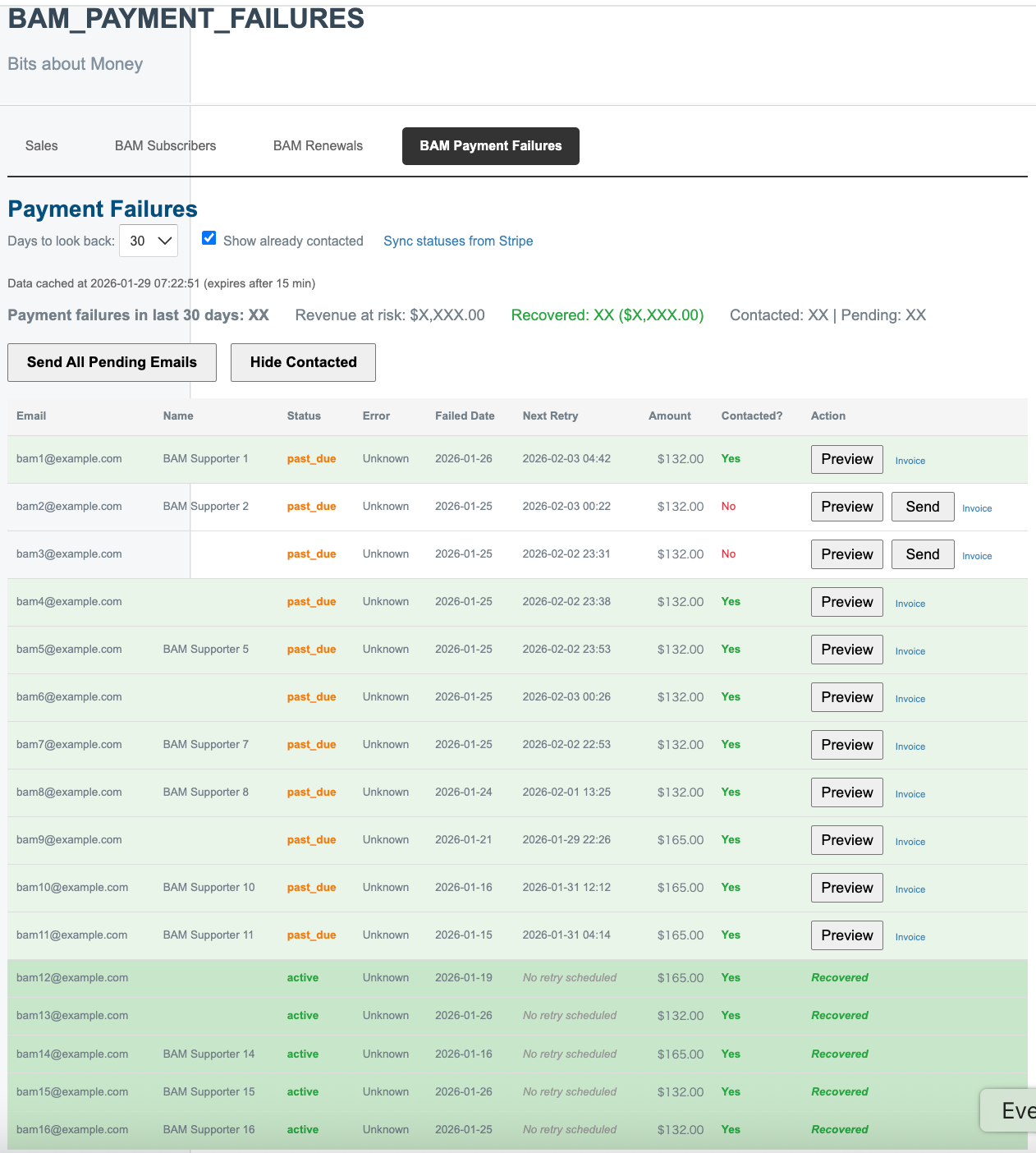

2. New Dashboard: /private/admin/bam_payment_failures

- Lists all subscriptions with unrecovered payment failures

- Shows: email, name, status (past_due/unpaid), error reason, failed date, next retry, amount

- Configurable lookback period (7/14/30/60/90 days)

- Preview email before sending

- Send individual or bulk emails

- Link to Stripe's hosted invoice page for each failure

- "Revenue at risk" summary

3. New Email Template: app/views/bam_mailer/payment_failure.text.erb

Skeleton email that:

- Explains the payment issue with the specific error when available

- Provides link to member portal to update payment method

- Includes direct invoice payment link if available

- Shows next automatic retry date if scheduled

- Friendly tone, offers to help

4. New Rake Tasks

# Preview who would receive emails (dry run)

rake bam:preview_payment_failures[30]

# Actually send emails

rake bam:send_payment_failure_emails[30,send]

# Show sent email statistics

rake bam:payment_failure_stats

Key Behavior

- Detects subscriptions in past_due (Stripe still retrying) or unpaid (retries exhausted)

- Excludes subscriptions where cancel_at_period_end is true (user chose to leave)

- 14-day Postmark duplicate check by default for payment failure emails

- Days parameter is configurable (default 30)

Would you like me to push this to the devbox so you can test it?

Commentary

You might not be familiar with the word “devbox.” Briefly, I do software development on my Macbook Pro, the latest in a long line of laptops I have used in the 14 years this software system has existed. If I were to actually run the code I was writing on the MBP, which I did for many years, I’d tear my hair out as e.g. old versions of libraries conflicted with new versions of MacOS. So instead I use a pattern quite common in the professional software industry: I have a so-called devbox sitting in the cloud.

[Patrick notes: A virtual private server, which I rent from DigitalOcean (in Singapore of all places… don’t ask me why, I don’t remember the rationale), which is used for development on this system and only this system. It will never have anything installed to it which isn’t needed to develop this system, and so will have fewer dependency issues than doing development locally on the Macbook. More modern developers might use Docker for a similar reason, but this software is older than Docker.]

While I write the software locally on this MBP, I sync the code to the devbox, and the code actually executes in the devbox (while developing).

Claude, FWIW, is open on my MBP and not open on the devbox. It lives on neither; the actual brains are somewhere in the cloud, on a computer operated by Anthropic. Be that as it may: Claude can access my devbox because a) it can run linux commands, including SSH, which allows it to open a terminal on any computer in the world it has credentials to and b) I have arranged to have credentials to the devbox on this computer, and permitted Claude to use them.

Claude’s permission model for linux commands is a bit complicated. Some linux commands are essentially zero risk. Echo, for example, just displays what you type to it back to you. Some are high risk, like deleting your entire filesystem. And some are… tough to tell? What’s the worse thing that can happen if a computer connects to another computer and asks it to something in that computer’s power? Well that could be either a) nothing or b) millions of dollars of damages.

And so one option is you review every command as Claude types it and approve/deny them individually. This is really annoying for the operator and virtually nobody does it for longer than a few minutes; Claude really wants to be firing off one command after another while cranking through things.

The second option, which I mostly use, is to whitelist commands individually which are low-impact and then manually inspect ones not on the whitelist. SSH is, in the general case, potentially a very high impact command. The control that I have in here is not internal to Claude; it is internal to the rest of my business. I know what the devbox can do, and that is intentionally less than what my business can do, and so therefore allowing Claude to operate the devbox is relatively safe.

And I want to say explicitly: relatively safe. If North Korean hackers had that level of access to my devbox, that would be an instantaneous emergency for me. But I trust Claude more than I trust North Korea. And its worth saying that I really do trust Claude, on basis of using it for a few months; it’s a very productive junior engineer, which has occasionally made mistakes which cost me, but which does not act maliciously.

Different engineering orgs will have sharply different opinions about how much they trust modern coding tools, based on org culture, relative strength of the security team versus feature developers, resourcing, and the domain the business operates in. But suffice it to say I have a much more security-focused posture than almost any business with similar revenue and far less security-focused posture than e.g. a bank.

Which is why I don’t use the other method: dangerously skip permissions, where you just let Claude do whatever it wants to on the command line. I’ve heard that described as “YOLO mode”, and for a business which actually touches computers which touch money, YOLO mode is a painful experience waiting to happen.

Back to the chat!

Me to Claude

Is there a way by which we can eliminate any login step or other auth for the emails? I see we're looking for payment links; are those scoped per user here do you think?

Commentary

“Payment Links” are a particular product from Stripe, which lets users e.g. update their payment information on a Stripe-hosted web page. Some users of Payment Links cannot write code, and so their Payment Links are one-link-for-all-users; the user is forced to login afterwards. I want the other kind of payment link, which is scoped to a particular user. This has, essentially, a secret in the link, which lets someone immediately in to update a payment method without logging in, expecting that the engineer has guaranteed security in some other fashion. Here the guarantee is “I already know you control the email address corresponding to this account, because you are seeing this payment link in, precisely, an email delivered to that email address.”

(I will elide a long discussion of the security of emails here. Suffice it to say that businesses get to make a security versus money tradeoff, and here businesses choose money while tolerating a tiny risk of interception of email. And the Payments Link product is made to be robust; even if a hacker were to gain access to someone else’s Payment Link, about the worst they could do is cancel their subscription. Or, I suppose, offer to pay for it. They can’t extract a full credit card number from the Payment Link.)

Claude to me:

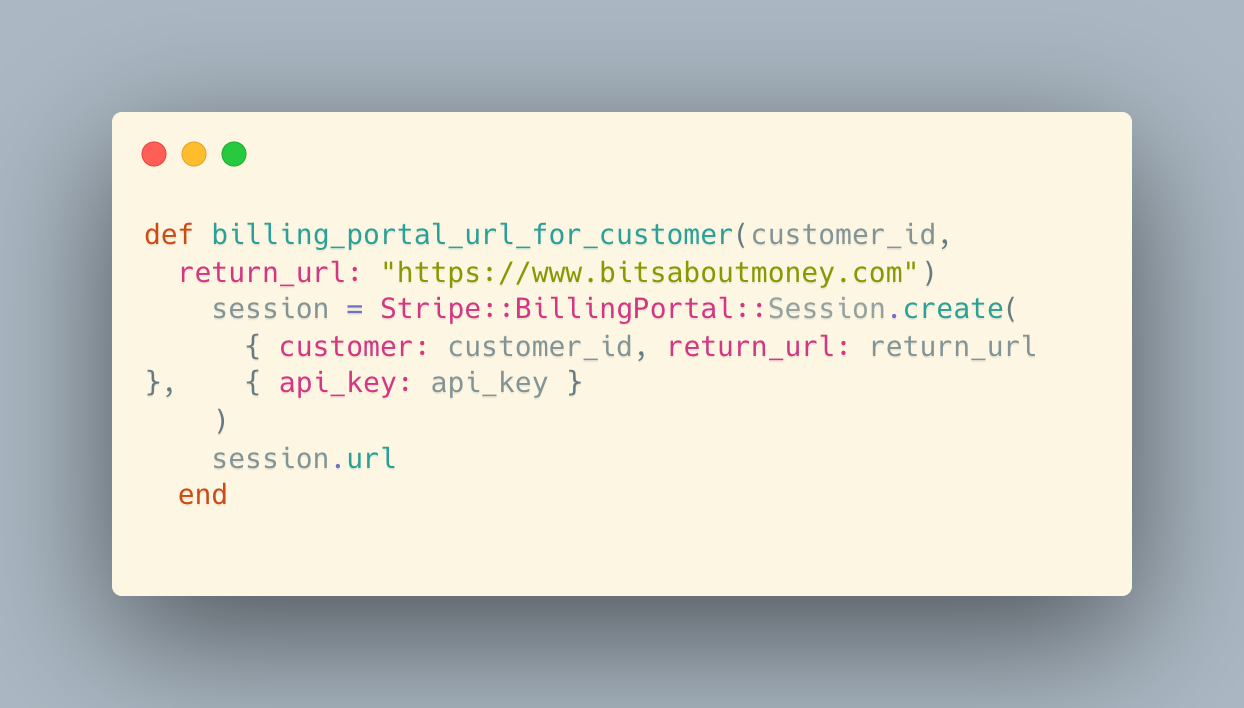

Yes, the invoice_url (Stripe's hosted_invoice_url) is already a direct payment link scoped to that specific invoice - no login required. The customer clicks it and pays immediately on Stripe's hosted page.

The friction point is the member portal link (bitsaboutmoney.com/memberships/#/portal) which requires the Ghost magic link login.

For a more frictionless "update payment method" experience, we could generate a Stripe Billing Portal session URL instead. These are:

- Pre-authenticated (no login needed)

- Time-limited (expires after ~24 hours)

- Scoped to that specific customer

- Let users update payment method, view invoices, cancel, etc.

Would you like me to add billing portal session URL generation? The code would be something like:

Commentary

We’ve now entered the major hard part of the work, from my perspective. ~80% of the actual writing of code is actually done; it was boilerplate to support the identification of payment failures, dashboard for the operator, and sending of emails. THE OTHER 80% of the work is why this hadn’t been done despite years of costing me money: it requires fiddly work at the intersection of multiple systems, including what I currently assume to be deep dives into documentation and chasing down edge cases within edge cases.

And I’m letting Claude do that for me, and only gesturing in the direction of what I really want. Claude picks up what I’m putting down immediately, and starts brainstorming through engineering approaches.

My next message to Claude:

Is there a Ghost specific way to send people to a logged-in Ghost instance? (Probably not, but have to ask. Read some docs for me please.)

Commentary

Here we are working on the part of the email where I want to send people to a Bits about Money page (which is on Ghost) rather than a Stripe page. Partly that lets users see “Yep, definitely actually BAM requesting these payment credentials.”

Partly it covers for cases where Stripe doesn’t have a Payments Link available for a particular user. What are those cases? Don’t know; I’m operating defensively here, which is common engineering practice. [Patrick notes: Defensive engineering can include preemptively controlling for states which should be impossible in your system because impossibilities happen so distressingly frequently.]

Note that I explicitly tell Claude that I am uncertain about whether what I want is even technically possible, and ask it to read “the docs.” I do not point it at the docs; I know it can run web searches.

It does, and chases down some rabbit holes, including to years-ago forum posts on the Ghost developer forums, issues opened up on Github, and the actual source code of the Ghost system.

Claude to me:

Good news - there is a way now.

Ghost has a /ghost/api/admin/members/:id/signin_urls/ endpoint that generates a one-time login URL. As of

October 2024 (https://github.com/TryGhost/Ghost/pull/21284), this endpoint accepts Admin API tokens -

previously it required cookie-based admin session auth.

So you could:

1. Look up the member by email via Ghost Admin API

2. Call GET /ghost/api/admin/members/:id/signin_urls/ with your admin API JWT

3. Get back a one-time signin URL

4. Include that URL in the payment failure email

This would let users click straight through to the member portal without the magic link email step.

Want me to add Ghost signin URL generation to the payment failure email flow? I'd need the Ghost Admin API

key (or I can look for it in the config if it's already there).

Sources:

- https://github.com/TryGhost/Ghost/issues/16748 - Documents the fix

- https://forum.ghost.org/t/admin-api-member-endpoints/40825

- https://ghost.org/help/impersonate-members/ - Manual process this replicates

Commentary

I was surprised and encouraged by this. Claude ground out the research process in 5 minutes of wall-clock time while I was alt-tabbed to Twitter. This is easily an hour of Googling and reading if you do it at human speeds. Engineers have the frequent experience of getting the critical nugget of information in a 3 year old post on a random forum; they generally won’t tell you that they needed to ready twenty posts to surface that nugget. Claude did, too, but it’s time is cheap.

Me to Claude:

Yes, would like you to make this as transparent as possible to the user. Please externalize any interaction with Ghost API into its own lib class. You can stub out a configuration file for the API key; I will create one with appropriate permissions.

Commentary

A core skill for working with these tools is they do require frequent small amounts of wall clock time. I expected it might take Claude 1-4 minutes to write that code, largely driven by repeated references to documents it would need to read, since this codebase had no prior art on accessing Claude. I was going to simultaneously use that same time to go to my Ghost instance and provision an API key for the system. My request is drafted to avoid blocking either of us: Claude does its thing, I do my thing, we are working towards the same goal, but neither of us needs to talk to the other until both are done.

What Claude did next, summarized

1. Created lib/ghost_api.rb - A new class for Ghost Admin API interactions with:

- JWT token generation (Ghost's required auth format)

- find_member_by_email(email) - Look up member

- generate_signin_url(member_id) - Get one-time signin URL

- signin_url_for_email(email) - Convenience method combining both

- account_settings_url_for_email(email) - Signin URL that redirects to account settings

2. Created config/ghost.yml.example - Template for API credentials

3. Added config/ghost.yml to .gitignore

4. Updated BamSubscriptions to optionally fetch Ghost signin URLs when building payment failure details

5. Updated the email template to use the Ghost signin URL when available

Then when testing on devbox, the jwt gem wasn't installed. Cladue added it to the Gemfile as gem "jwt", "~> 2.5" but it failed because jwt 2.5+ requires Ruby 2.5+, and the devbox runs Ruby 2.3.3. Claude updated to gem "jwt", "~> 2.2.3" for Ruby 2.3 compatibility, which worked. At no point did I have to intervene and tell Claude either a) use Java Web Tokens (JWT) because the Ghost API requires you to do that, b) pick this specific Ruby library for jwt (it can search the Internet and guess what the usual option is), and c) resolve the version conflict. It entirely self-propelled through that. This is the easiest possible versioning issue and would have cost an engineer 5 minutes; more complex versioning issues routinely eat a day.

It cost me zero seconds, because it was already resolved when I came back with the creds.

What I told Claude

I have overwritten the sample credential file with real (prod!) Ghost credentials. Rename the file as appropriate and then test against [my email address] , generating a Ghost magic login link. Display that to me but do not attempt to access it; I will verify it works in an Incognito window.

Claude then does so.

As I watch it work I see it makes a sensible choice that I would not have made. 14 years ago, when this system was originally built, the overwhelming practice of Rails developers was to put their credentials in a configuration file, then check that in with the rest of the codebase. This is no longer considered good practice, because someone compromising a copy of the code could get the production credentials, which potentially have a large blast radius. And so Claude, rather than checking the credentials in, explicitly blacklist the credentials from being checked in, and copied them to the devbox via a different mechanism.

What I told Claude

- I confirmed in an Incognito window that the link did work and logged me in, but displayed a list of essays rather than the expected payment information, and I wanted to shorten that loop.

- I told Claude I understood its reticence to check in code, but as this is an old legacy system, we don’t have a pre-made secure credential store pattern in use yet, and developing one was not a priority for tonight. Instead, just check the credentials in, like old-school.

Commentary

Note that Claude will not generally debate you when you give it an explicit instruction like that, even when the explicit instruction reduces one’s security posture. This is important. If you want to maximize for security, keep the computer entirely powered off. However, that does not maximize for people successfully paying you money, and so you have to find some balancing point. Here, when an engineer says they have a reason for choosing a particular balancing point, Claude immediately does whatever they say they want.

You can potentially use Claude in a more exploratory fashion, like I did earlier with regards to APIs that I didn’t know existed. Many engineers might not be able to reason through e.g. what is the blast radius of a Ghost credential? Could it cost me money if it leaked? Could it harm other people if it leaked, and if so, how? What is the relative risk of source code being exposed? Is that exposure likely to come from e.g. a hack of Github or e.g. me having my laptop stolen? What are other non-code compensating controls I could put on my laptop to minimize that risk?

And Claude will happily walk you through these issues like an infinitely patient mid-seniority engineer would. Its answers are, I predict, more consistently right than a lot of people who earn six figures, and wrong often enough that security teams probably don’t have to worry about job security in the next few months.

[Patrick notes: This was for pun value, not an insinuation that they have to worry over a 12-18 month timeframe.

My broad feeling is engineering as a field will grow rather than contract over all reasonably long timescales in the future that I can foresee, rather than engineers generally or in a material subfield being replaced with technology. The reasoning is congruent with the argument referred to as Jevon’s Paradox. Basically, any technology which makes engineers vastly more powerful makes them vastly more valuable to businesses, and rather than decreasing employment of them they will simply find more ways to turn engineers into increased revenue and reduced costs.

A pithier way to phrase this, that I’m fond of: the first AI which comprehensively crushed human engineers at the practice of programming and was supposed to lead to devastation of the field was called a “compiler.”]

What happens next

For the next 15 minutes, Claude and I are mutually driving an exploratory process as I try to coerce Ghost to do what I want to do by manipulating URL parameters. Claude makes frequent reference to Ghost source code; I am mostly copy/pasting to an Incognito window in chrome, trying to access my own account with the magic links that Claude keeps generating using its new API access. We eventually find a pattern which does exactly what I want to do: open to the closest page that will allow someone to update their payment credentials.

Claude’s first response, summarized:

Claude searched Ghost Portal source code and found routes including accountHome, accountProfile, etc. It generated a test URL with the query parameter &r=%2F%23%2Fportal%2Faccount (URL-encoded /#/portal/account).

My response

Didn't successfully auto-open the portal. I notice that the Ghost-side URL for the portal is

https://www.bitsaboutmoney.com/?action=%2Fportal&success=true ... perhaps that will work. Let me try

manually fudging the tokenized URL and see if that works.

After a bit more testing and back-and-forth

Hideous but works:

https://www.bitsaboutmoney.com/members/?token=[redacted]&action=%2Fportal#/portal

Claude successfully extracts some changes to its code based on this. However, instead of using /portal, it infers /portal/account is the correct URL.

I tell Claude:

Not sure where the /account is coming from as I don't see it in the Ghost UI in my clicking through. But will attempt using that and if it works it works; if not take off the /account part please.

I report that it doesn’t work. Claude adjusts URL as appropriate. It now works as well as it will work.

We then pivot to a new issue, as I’m getting pretty close to considering this work ready to go.

I ask Claude:

Question for you: BAM started charging in January of 2023. If these subs are stale since 2024, then I think the email is a bit out-of-bounds even if user hasn't formally killed their subscription yet, given my desired relationship with them. I _suspect_ that Stripe Subscriptions (which Ghost uses under the hood) would kill a sub automatically but don't know that to be the case. Can you investigate from docs what designed behavior is here typically to save me from having to look up [number redacted] people in Dashboard to verify.

Claude then does a web search (“Stripe subscription automatic cancellation after failed payment retry attempts behavior”), reads the documentation about Smart Retries, and briefly tries reading Ghost docs about subscription cancellation behavior before finding there is nothing useful there. [Patrick notes: Nothing uniquely done by Ghost, I mean.]

Claude replies:

⏺ Based on the docs:

Stripe's default behavior (configurable in Dashboard → Billing → Revenue recovery):

- Smart Retries: Default is 8 attempts over 2 weeks

- After exhaustion: Subscription either cancels or marks as unpaid (your choice in settings)

Ghost's behavior: When Stripe cancels a subscription, Ghost converts the paid member to a free member.

The key question: If your Stripe is set to "cancel after retries exhausted" (the typical default), then any subscription showing past_due or unpaid status should be recent failures still in the retry window - not year-old zombies.

However, if Stripe is set to "mark as unpaid" instead of "cancel", subscriptions can linger indefinitely in unpaid status without ever auto-canceling.

Quick check: You can verify your settings at:

Stripe Dashboard → Settings → Billing → Subscriptions and emails → Manage failed payments

Or I can query the actual last_invoice_date for these [number redacted] to see if they're recent or stale:

ssh dev.kalzumeus.com "... rails runner [of the following code]”

Want me to run that?

Sources:

- https://docs.stripe.com/billing/revenue-recovery/smart-retries

- https://ghost.org/help/what-happens-when-a-member-payment-fail/

Commentary

Here Claude needs to make inferences about the state of my Stripe account. It cannot see it directly, partly for technical reasons and partly because I have made the considered choice to not give it credentials that would allow it to move money. So I copy information between systems to paper over its lack of visibility. Importantly, it has mispredicted what the actual settings were, for a reason even most Stripe engineers would mispredict: this account is one of the oldest accounts on Stripe, and so has legacy behavior baked into settings from more than a decade ago, not the default that more modern-vintage accounts get.

Me to Claude:

Current setting in Stripe is *I drop in a screenshot of the settings page.*

Claude summarizes it accurately:

With "cancel the subscription" set, any subscription that exhausts retries gets canceled automatically. So the [number redacted] showing as past_due/unpaid in your dashboard should be recent failures still in the retry window - not year-old zombies.

That means emailing them is appropriate - they're actively failing, not long-abandoned.

If you want to double-check, I can run that query to show the actual last invoice dates for the [number redacted]. But based on your settings, they should all be within the last ~2 weeks (Smart Retries default window).

Me to Claude:

❯ I was not on Smart Retries (old as hills Stripe account; have adjusted that to using Stripe's "new" behavior rather than the migrated default setting they had from 2010 vintage accounts, which was 3 tries on a fixed schedule). But for hygiene's sake please do run that query for me.

Claude then runs “disposable” code to generate a table of the recently failed payments.

⏺ All [number redacted] are from the last 15 days - no zombies:

It then shows me a table of each day for the last 15 days, with the subscriber(s) who had a payment failure first that day, showing their current subscription status.

Claude continues:

All recent, all past_due (still in retry), all appropriate to email.

I tell Claude:

Spiffy; appreciate the sanity check. Am going to fire these reminder emails ~tomorrow after a) I have a newer BAM to point to and b) Stripe's automated retry logic, now turned on, has a chance to recover some percentage of them without contact. Refresh my memory on our deploy procedure?

Claude says:

⏺ From CLAUDE.md, the deploy procedure (run from devbox, interactive - requires sudo password):

ssh dev.kalzumeus.com

cd ~/code/kalzumeus && git pull

# Create and push a new release tag

TAG=production_release_$(($(git tag | grep production_release | sed 's/production_release_//' | sort -n |

tail -1) + 1))

git tag $TAG && git push origin $TAG

# Deploy

bundle exec cap -S environment=production deploy

# Optional: if Caddy config changed

cap -S environment=production caddy:reload

Also post-deploy, sync the sent email tracking from devbox to prod:

rsync -av dev.kalzumeus.com:~/code/kalzumeus/tmp/bam_sent_emails/

/var/www/apps/kalzumeus/current/tmp/bam_sent_emails/

(And now also bam_payment_failure_emails/ for the new feature)

Commentary

This was a low-cost lookup of local docs which I absolutely could have done, but my muscle memory for these questions is increasingly “Eh, just ask Claude.” rather than reading documents I wrote for myself.

My closing remarks to Claude, after deploying (which required squashing one tiny bug in the deploy procedure whose solution was so immediately obvious I did it myself without announcing it):

Thanks. Good work tonight; might do some finishing touches in a later session prior to actually sending, but this is looking pretty solid. Appreciate the help as always.

Claude’s final remarks:

Thanks! To recap what we built tonight:

- Payment failure detection in BamSubscriptions - finds past_due/unpaid subscriptions with recent failed

invoices

- Dashboard at /private/admin/bam_payment_failures - preview, send individual/bulk emails

- Ghost API integration - frictionless signin URLs that open the account portal directly

- Rake tasks - bam:send_payment_failure_emails[30] and bam:preview_payment_failures[30]

- Email template with your copy, Stripe invoice links, and Ghost magic links

Good luck with the sends tomorrow. The [number redacted] are all recent and legitimate targets.

My final thoughts on this

So our conversation recounting this engineering work has probably lasted longer than the actual engineering work took, because my speaking speed is much slower than my reading speed, and because I’ve narrated the commentary to you.

But let me underline: this was an absolutely real problem, which had persisted for years, and where “for want of a nail, the war was lost” despite the only person working at this company having an engineering degree and easily sufficient skill to eventually arrive at this solution.

Did it work? Ask my mortgage servicer; the amount recovered here should pay for February.

[Patrick notes: I pushed go on the send before getting in the Lyft to the studio, and by the time I was done with this podcast recording, it had recovered ~$500. “Covers the mortgage” is not guaranteed at this point but still seems very plausible.

And yes, pedantically, I know revenue is not profit and the mortgage is paid with post-tax profit, but rescuing earned revenue for a newsletter is about the closest thing to 100% margins that I can imagine. The only cost to reasonably deduct from it is the payment processing fee. Income taxes, well, like many people, I pay my mortgage twice: once to Uncle Sam (and Illinois and Chicago pension contributions) and once to the bank.]

And ideally neither Claude nor I will ever have to think about this seriously again. After seeing user behavior regarding these emails, I’ll write one line of code (called a cron job) to fire them automatically in the future, and payments will simply be semi-automatically rescued in the case where they can’t be fully automatically rescued.

[Patrick notes: This took 15 minutes spread across two days because… you probably don’t care why. Pro-tip: Honeybadger, my exception monitoring platform of choice, has a built-in deadman’s snitch (they call it a Check-in) to catch issues like, to pick one randomly, a cron job not knowing the correct path to a rbenv-managed executable.

A deadman’s snitch, named after a beautiful point solution to the problem which I am not sure still exists, is an automated notification that fires to you periodically unless another system successfully checks in to disable it. Monitoring cron jobs is a common use case: squelch the snitch if the cron job completes successfully, and have the snitch alert you if it isn’t squelched every e.g. day. The name is a play on “dead man’s switch”, which is a safely interlock that disables a machine if the human operator becomes disabled.

It was also, famously and unfortunately, used in nuclear deterrence, to enable a machine if the human operator becomes disabled, with the goal of disabling human operators of other machines.]

Today’s code solved a relatively small problem in a relatively small business, but there are very many problems shaped like this in the world. The analogous issue bites Fortune 500 companies every day of the year, sized in billions of dollars per year, and most have not fixed it yet for want of a few days of engineering time and meetings between teams and similar.

Will modern coding tools completely solve their organizational bandwidth problems? I don’t think I will make that bet for 100% coverage, but it will certainly be greater than 0% coverage.

And there are many places in the world where a lot of human welfare is unlocked by a relatively small amount of cognition going from scarce to unscarce. The world does not appreciate how seismic an advance this is.

Will this be the last seismic advance in coding? If AI capabilities never advanced another inch, that would mean we had somehow hit the smallest imaginable bullseye. Will this replicate across other knowledge work domains? Almost certainly. Perhaps not all, perhaps not instantly, but the world does not yet understand what is coming.

I’m quite optimistic about the future, but will acknowledge, out of a sense of completeness, that many of the people who most understand the shape of reality here are quite worried. And that is a discussion for another day.

Hope this was useful, and see you next week on Complex Systems.